Language Characteristics of Children with ADHD

Language Skills in Kids with ADHD vs. Kids Without

Okmi H. Kim, Ann P. Kaiser

Objectives

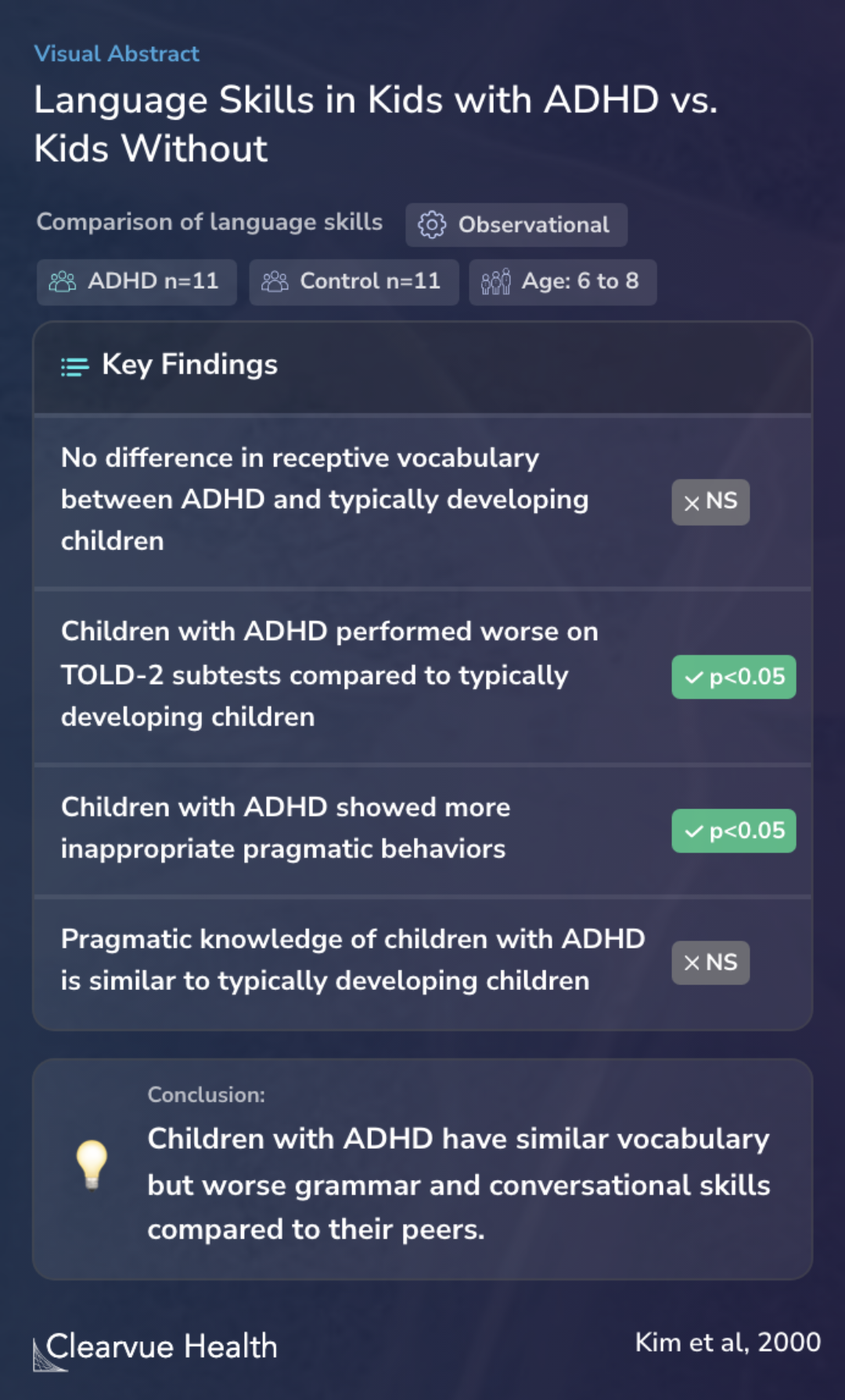

The paper set out to explore how 11 children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and 11 children without this diagnosis, all between the ages of 6 and 8, use language. Specifically, the authors wanted to understand if there were any notable differences in the way these two groups of children use words (semantic skills), put sentences together (syntactic skills), and use language in social situations (pragmatic skills).

Language characteristics of 11 children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and 11 typically developing children ages 6 to 8 were compared in terms of semantic, syntactic, and pragmatic language skills.

Methods

The study was designed to observe and compare language skills between two groups of children, one with ADHD and the other typically developing. The researchers used several tests to measure different aspects of language. The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R) helped them understand the children's vocabulary knowledge. The Test of Language Development-2 Primary (TOLD-2) was used to evaluate more in-depth language skills like sentence construction and word articulation. Lastly, the Test of Pragmatic Language (TOPL) assessed how well children used language in social contexts. During the study, the children engaged in free play sessions with an adult, during which their conversations were analyzed to see how they used language in real-life interactions.

Children were tested on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R), the Test of Language Development-2 Primary (TOLD-2), and the Test of Pragmatic Language (TOPL). Samples of children's language were collected during free play with an adult conversational partner using the Prag...

Results

The study's findings revealed that when it came to understanding and using vocabulary (receptive vocabulary), there wasn't a noticeable difference between children with ADHD and those developing typically. However, the story changed when looking at more complex language skills. The ADHD group found it more challenging to imitate sentences and articulate words, and overall, their speaking and language abilities were not as strong as their peers without ADHD. In conversations, these children also showed more inappropriate behaviors, even though their understanding of social language rules (pragmatic knowledge) seemed on par with the typically developing group.

Results indicated that there was no difference between the two groups on receptive vocabulary as measured by the PPVT-R. Children with ADHD performed worse than typically developing children on the sentence imitation, word articulation, speaking quotient, and overall speech and language ...

Conclusions

The findings from this paper indicate that while children with ADHD might understand words just as well as their peers, they tend to struggle more with grammar and using language effectively in conversations. This suggests that their challenges lie more in the realm of expressing themselves and interacting socially rather than in basic language comprehension.

Results are discussed in terms of the relative strengths and weaknesses in the communication skills of children with ADHD.

Key Takeaways

Context

Other research supports the idea that language skills are crucial for social interactions, especially for children with ADHD. For instance, a study by Staikova et al. in 2013 found that children with ADHD often have difficulties with the kind of language skills needed for socializing, which can make it hard for them to form friendships.

Other studies have dived deeper into ADHD, comparing some of the effects to autism: