Social functioning in children with ADHD treated with long-term methylphenidate and multimodal psychosocial treatment

Effects of Social Skills Training and Medication for ADHD

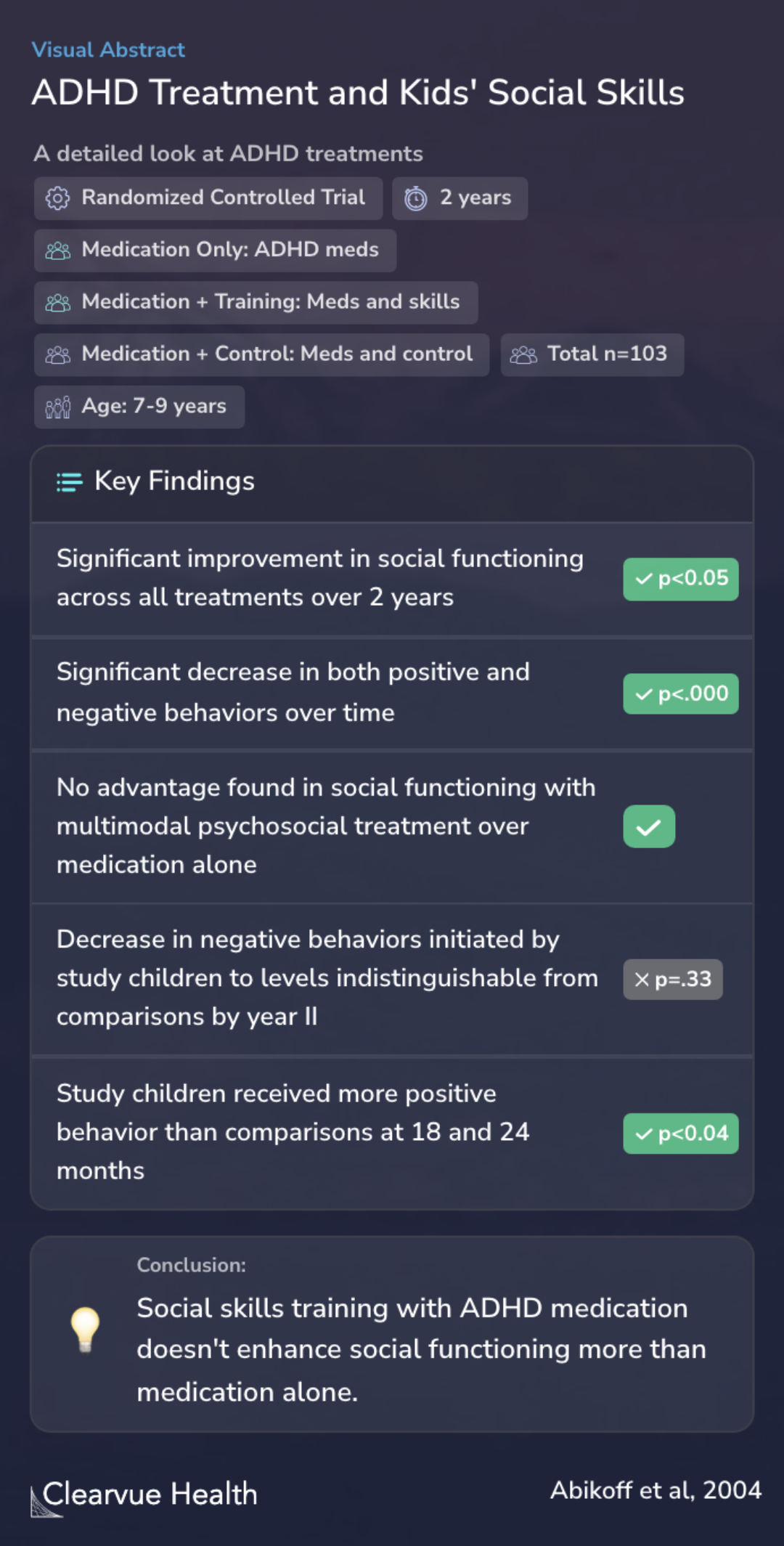

Abikoff H;Hechtman L;Klein RG;Gallagher R;Fleiss K;Etcovitch J;Cousins L;Greenfield B;Martin D;Pollack S;

Objectives

The study aimed to explore whether combining the medication methylphenidate, the generic form of Ritalin, with a special training program that teaches social skills could help children with ADHD interact better with others than just giving them the medication alone or with a different kind of non-specific support.

To test that methylphenidate combined with intensive multimodal psychosocial intervention, which includes social skills training, significantly enhances social functioning in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) compared with methylphenidate alone and methylpheni...

Methods

In the study, 103 young kids aged 7 to 9 who have ADHD but do not have serious behavior or learning problems were given methylphenidate (Ritalin). They were then divided into three groups for two years. One group was given just the medication, another group got the medication along with a special program to help them with social skills, and the last group received the medication and a different kind of non-specific support. To see how well the treatments worked, the researchers looked at ratings from parents, children, and teachers about the kids' social behavior. Also, they watched how the kids acted at school, especially during playtime.

One hundred three children with ADHD (ages 7-9), free of conduct and learning disorders, who responded to short-term methylphenidate were randomized for 2 years to receive (1) methylphenidate alone, (2) methylphenidate plus multimodal psychosocial treatment that included social skills tr...

Results

The study found that adding special social skills training to the medication didn't make the kids act better socially compared to just giving them the medication alone or with non-specific support. However, all the treatments did help improve the kids' social skills over the two years. Both good and bad behaviors changed for the better during this time.

No advantage was found on any measure of social functioning for the combination treatment over methylphenidate alone or methylphenidate plus attention control. Significant improvement occurred across all treatments and continued over 2 years.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that for young kids with ADHD, teaching social skills at a clinic as part of a long-term treatment plan doesn't really make their social behavior better compared to just treating them with medication. The positive effects of the medication were consistent over the two-year period.

In young children with ADHD, there is no support for clinic-based social skills training as part of a long-term psychosocial intervention to improve social behavior. Significant benefits from methylphenidate were stable over 2 years.

Key Takeaways

Context

Other research also shows that teaching social skills might not be that effective for kids with ADHD. One study from 2019 found that this kind of training doesn't really change how kids and teens with ADHD act or how well they get along with others.

Another study from 2018 suggested that the real problem might be that kids with ADHD know the social skills but struggle to use them consistently. Kids with ADHD might already know what they should do in social situations, but their symptoms might be getting in the way of them doing it.