The Persistence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Into Young Adulthood as a Function of Reporting Source and Definition of Disorder

ADHD patients underestimate ADHD persistence rates

Russell A Barkley, Mariellen Fischer, Lori Smallish, Kenneth Fletcher

Background & Methods

While most with ADHD see improvement over time, some continue to have ADHD into adulthood.

Studies have linked persistent ADHD with significantly worse outcomes and challenges at school and home.

However, it can often be challenging to diagnose and estimate rates of persistent ADHD.

This study wanted to compare rates of persistent ADHD, as measured by those with ADHD and their parents.

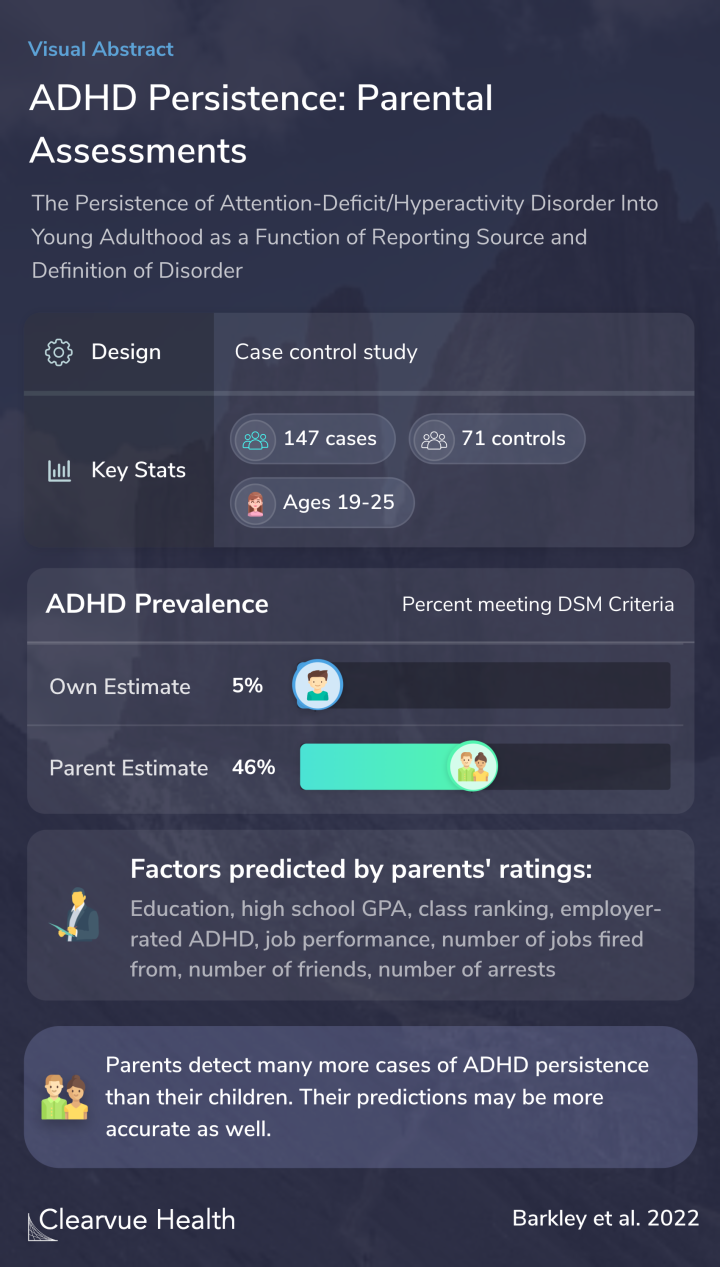

This study examined the persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) into young adulthood using hyperactive (N = 147) and community control (N = 71) children evaluated at ages 19-25 years.

Results

Researchers found that generally, the majority of those with ADHD felt that they were much better by the time they were adults. Based on the subjects' estimates, over 90% of those with ADHD no longer met the criteria for ADHD as adults.

However, when researchers asked parents to rate their child’s symptoms, over 40% of the same individuals still met the criteria for ADHD as adults. This means that, according to their parents, most children with ADHD continue to struggle as adults, even though they may not notice it themselves.

The large gap between parents' and the patient’s perceptions begs the question, who is correct? Do parents remember symptoms that aren’t there anymore, or are their children blissfully unaware?

To answer this, researchers gathered data on performance at school, at work, and at home. They used metrics that those with ADHD are known to struggle with.

They found that the parents’ ratings of their children were much more predictive of a child’s performance in life than their own rating.

This suggests that parents are probably better at telling whether their children have recovered from ADHD than the children themselves.

ADHD was rare in both groups (5% vs. 0%) based on self-report but was substantially higher using parent reports (46% vs. 1.4%). Using a developmentally referenced criterion (+2 SD), prevalence remained low for self-reports (12% vs. 10%) but rose further for parent reports (66% vs. 8%). P...

Conclusions

Diagnosing ADHD often involves collecting information from the patient, the parent, and potentially from school. This study provides evidence for the importance of input from parents. Parents often see things in their children that children don’t see in themselves.

These results also have important implications for studies on ADHD persistence. Many studies rely on participants' recollections and self-assessments of their ADHD symptoms.

The data in the study suggests that if we don’t also collect information from parents, we may be underestimating ADHD rates in adults.

The authors conclude that previous follow-up studies that relied on self-reports might have substantially underestimated the persistence of ADHD into adulthood.