covid-19 and heart attack trends: the risk of delaying care

Heart disease is the leading case of death in the United States. COVID-19 data scientists predict the virus will be the third leading cause of death in the United States this year. Both heart disease and COVID-19 patients face serious complications that often require immediate action. Unfortunately, the United States healthcare system was not prepared for the pandemic. When cases peaked in communities across the nation, their hospitals ran out of beds, the doctors ran out of protective gear, and there weren't enough ventilators to go around. This is still happening today. While medical systems struggle to keep up with COVID-19 demands, individuals with non-communicable diseases are falling behind in their care. People with diabetes are more likely to ration their insulin, and cancer screenings have been postponed. Likewise, people with heart attack symptoms are less likely to seek swift, life-saving treatment.

Changes in heart attack hospitalizations during the pandemic

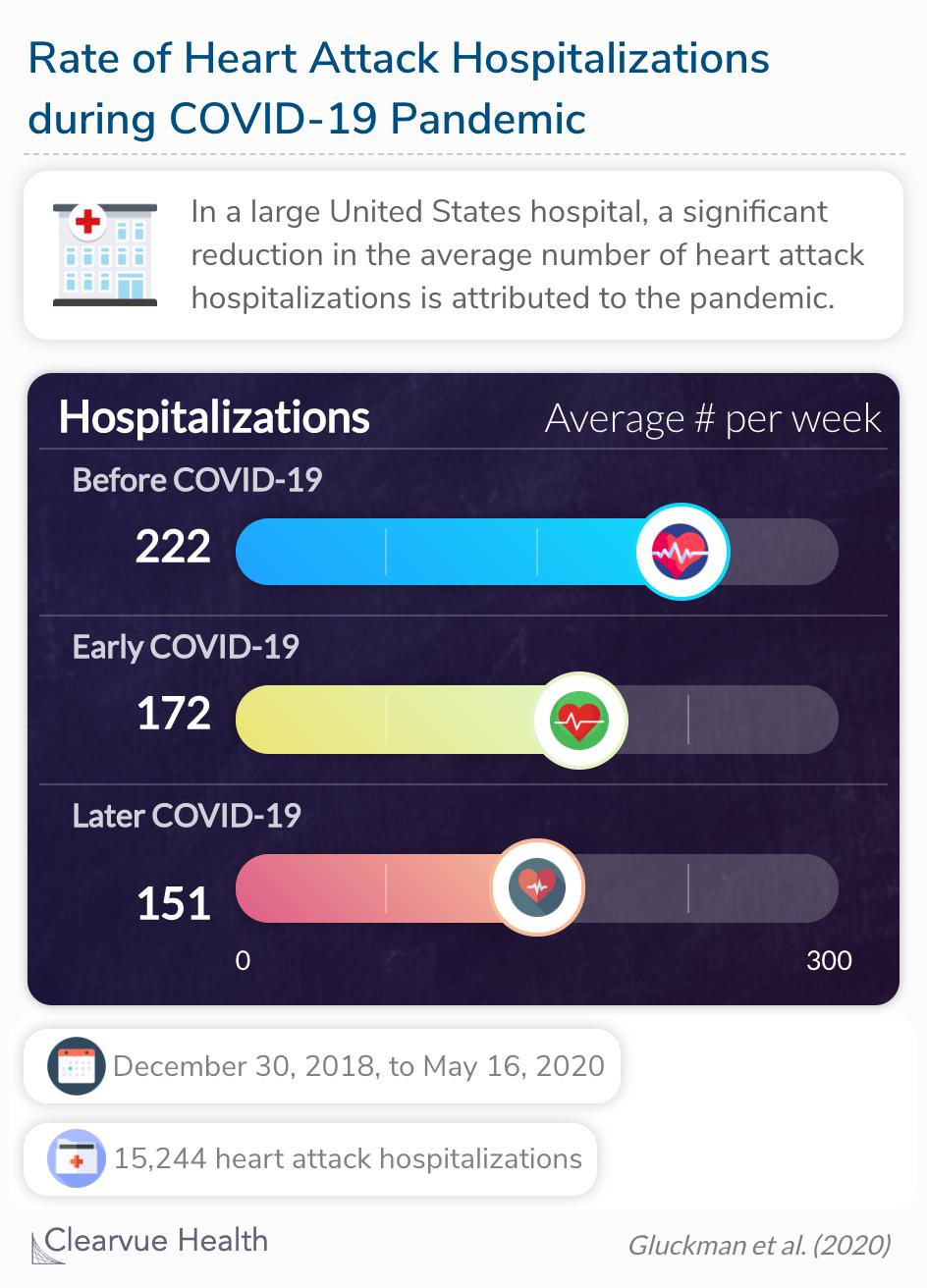

Heart attacks require specialized treatment from emergency physicians and cardiologists to restore blood flow to the heart. All patients experiencing a heart attack are instructed to call 911 or go to a cardiac care center immediately. Researchers used data from these medical centers to quantify the pandemic's impact on heart attack hospitalizations.

Beginning February 23, 2020, AMI-associated hospitalizations decreased at a rate of –19.0 (95% CI, –29.0 to –9.0) cases per week for 5 weeks (early COVID-19 period).

Source: Case Rates, Treatment Approaches, and Outcomes in Acute Myocardial Infarction During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic

In the early phases of the pandemic, heart attack hospitalizations decreased by 19% over a 5-week period. After that, heart attack admissions began to rise again but did not reach its expected rate as of late May. A reduction in hospitalizations is not a reduction in cases; it is a reduction in cases that are appropriately treated. This rise in inappropriately or untimely treated heart attacks is shown in heart attack mortality rates.

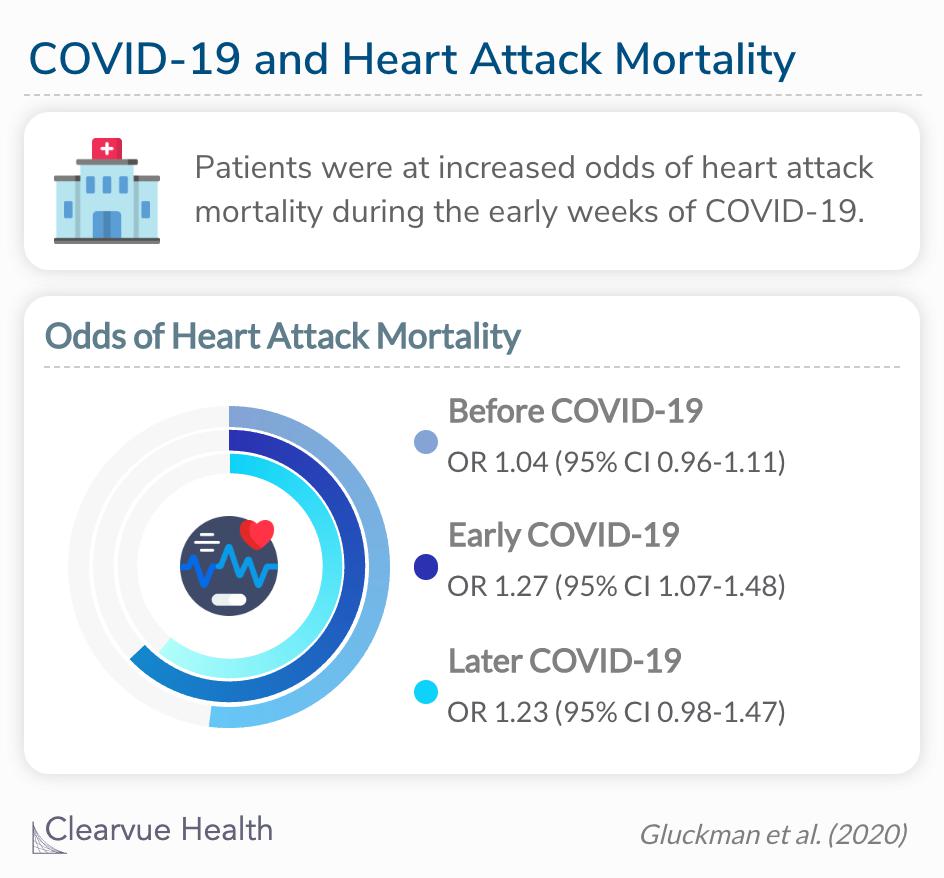

Patients were at increased odds of heart attack mortality during the early weeks of COVID-19 (OR 1.27, 1.07-1.48).

Among all heart attack patients included in the analysis, patients hospitalized in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic had 27% increased odds of heart attack mortality. Heart attack patients from the weeks before COVID-19 had an insignificant, average risk. Later COVID-19 patients failed to reach statistical significance but still leaned toward a higher risk of mortality.

“

Possible explanations for these findings were greater reluctance by older patients to seek medical attention, hospital efforts to maintain bed availability, patient preference for early discharge, and concern about risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 in post–acute care facilities.

JAMA

Heart attack trends since 1999

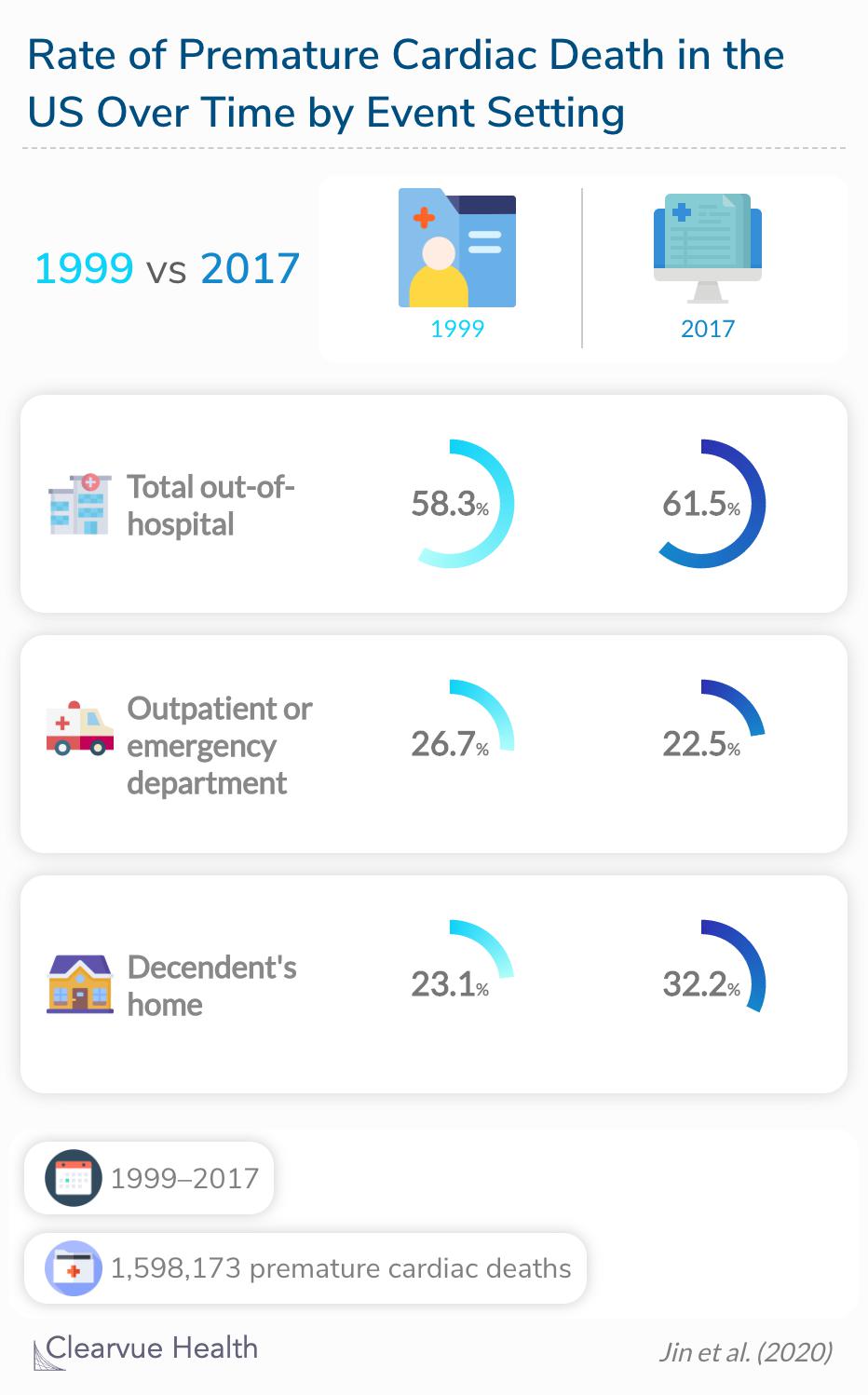

A reluctance to go to the hospital for chest pain or other early heart attack symptoms is not a new phenomenon. A recent study calculated the rate of premature cardiac deaths in the United States since 1999 that highlights this fact.

From 1999 to 2017, although the age‐adjusted rates of PCD decreased, the overall proportion of out‐of‐hospital rates among PCDs increased slightly from 58.3% to 61.5%.

Source: Disparities in Premature Cardiac Death Among US Counties From 1999–2017: Temporal Trends and Key Drivers

From 1999 to 2017, the total rate of out‐of‐hospital premature cardiac deaths increased a small yet significant amount. In addition, deaths that occurred in outpatient or emergency department settings decreased, while home deaths increased. Researchers attribute these changes to low awareness of heart attack symptoms and the delay of seeking emergency medical services. As you can see, the reasons for the decrease in heart attack hospitalizations are similar to the barriers intensified during the pandemic.

Final thoughts

It is possible that the incidence of heart disease is increasing. People are falling into bad eating and exercise habits while stuck in quarantine and stress has skyrocketed, which can both increase a person's risk of a heart attack. Some researchers believe that people experiencing heart attack symptoms may be confusing them with COVID-19 symptoms. Some of the signs of a heart attack, such as pain in the chest and upper body, sweating, nausea, fatigue, or trouble breathing, also align with symptoms of COVID-19. However, these are not the most common hypothesis for the increase in at-home cardiac deaths.

The most common theory is that people are worried about contracting the virus. To this point, many medical centers and public health messaging in the early stages of the pandemic advised patients to postpone non-urgent medical care and keep urgent care and emergency medical staff available for an influx of COVID-19 patients. Coveractively, patients were left to determine the urgency of their medical conditions without professional advisement. Now, with all the revised messaging about COVID-19, it is likely that community understanding of hospital and safety protocols are questionable. The American Heart Association issued a statement in hopes of clearing up any confusion.

“

Calling 911 immediately is still your best chance of surviving or saving a life. It is SAFE for EVERYONE to call 911. It is SAFE for ANYONE to go to the hospital. From dispatchers to first responders, the emergency response system is trained to help you safely and quickly, even during a pandemic. Hospitals are following protocols to sanitize, socially distance, and keep infected people away from others. In fact, many now have separate emergency rooms, operating rooms, cardiac catheterization rooms, and ICUs for people with COVID-19, and for people without.

American Heart Association